|

July is fast approaching. The peafowl dating competition has passed. They're back to being sociable, hanging out in small groups. Peachicks are hatching and their mamas parade them with peacock escorts. We were cameraless the day we spotted six chicks, five brown, one white. Florida's already faced four tropical systems. The most recent, Debby, clung to the state like an unwelcome guest. Rivers overflowed. The Gulf of Mexico laughed at seawalls and much of the state is underwater. The storms are scary but awe-some . . . nature unleashed.  What does a writer in Florida do when it's storming? We head to the library, of course! This was shot outside our regional library last weekend during a milder moment in Tropical Storm Debby's visit. There's something comforting about gathering in a place filled with books, umbrellas dripping in a corner, rain pelting the windows while readers get lost in stories.

2 Comments

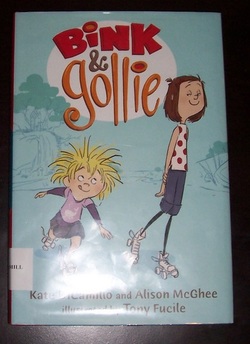

I'm continuing my summer review of books. Today, it's an early chapter book and I'm already breaking the promise I made to only cover books available in audio versions. I cannot be trusted when tempted by irresistible books. Bink and Gollie made me do it! Even though they lack an audio version, non readers will enjoy the fun interactive links on their website. I dare you to go there and not giggle. Kate DiCamillo, one of my favorite authors teamed up with Alison McGhee to write Bink and Gollie and they've recently released a second book, Bink and Gollie: Two for One. Award-winning illustrator, Tony Fucile captured the authors as children in Bink (a petite Kate with wild blond hair) and Gollie (a tall, thin Alison in managed, brown locks). The art is done in dynamic strokes, simple washes and minimal color. Unlike other early chapter books where the art merely illustrates the story, the art in Bink and Gollie is essential to the plot. The book offers vignettes in three chapters: Don't You Need a New Pair of Socks, P.S. I'll Be Back Soon, and Give a Fish a Home. Bink is a cheerful, impulsive girl who zips around town in roller skates and a skirt. She lives in a rustic cottage at the base of a tree, likes colorful socks and peanut butter sandwiches. Gollie lives in a minimalist, ultra-modern house in the tree's branches. She likes long words, mental stimulation and pancakes. In the first chapter, the girls happen upon a sock sale. Bink finds the perfect pair of socks and Gollie says, "The brightness of those socks pains me. I beg you not to purchase them." Bink hugs the socks and responds, "I can't wait to put them on." Their differences try their friendship in comical ways but their bond is never broken. Bink and Gollie won the 2011 Theodore Seuss Geisel Award and they have stolen my heart. In April I attended a workshop led by author and writing coach extraordinaire, Joyce Sweeney. The workshop focused on character but Joyce also critiqued first pages. Since many attend summer conferences where first pages are often reviewed, I thought I'd share what I learned from Joyce about that all-important start to a book.

This is my fifth year dedicated to learning to write and beginnings still feel like my nemesis. I revisit them repeatedly, experience "aha" moments when I think I've found the perfect opening only to see it dashed in critique. How do you accomplish all that's required in two-hundred and fifty words? Readers need to meet the protaganist and it isn't a casual introduction. They want to know their personality, age, their goal and conflict, where they live and when. They might also meet secondary characters. They'll need to know their relationship to the main character and what distinquishes them. For that reason, I try to keep the characters on the first page to a minimum. You don't want readers scratching their heads over who's who. On top of all that, the opening reveals the event that changes everything for the MC, the moment that sets the story in motion. That moment might be your HOOK! (yes, it is spoken in capitals. With an exclamation mark). Writers learn early about the need to snatch readers and reel them in. Huge units of brain power are burned trying to create irresistible openings. You have one, maybe two paragraphs to convince readers to buy your book. So, you promise thrills or chills or mind-shifting worlds. Which brings me to the first new tidbit I gleamed from Joyce's feedback: Genre should be evident from the start. If you're writing a ghost story, introduce spooky; if it's dystopia, show us the altered world; if contemporary, place us in the now. This is something I've ignored. I focused on character, conflict and setting, expecting readers to discover genre on the next pages. It's seems obvious now . . . if I'm expecting sci-fi and I find none on the first page, why would I read the book? The second discovery I made at the workshop was about character introduction. Readers need to relate to the main character, even want to be the character. So Joyce advised against showing their big flaw on the first page. The example she read opened with a protagonist who vomited when she was nervous . . . and she did it on the first page. It was a well-written scene but would you turn that page? You want the reader to like/admire/feel-compelled-to-follow the character before you introduce flaws that make them gag on the chocolate they're munching. First page reviews at conferences and workshops offer authors professional feedback. Eventually, your book will be submitted to agents and publishers and the industry is too overworked to read past a manuscript's unimpressive start. In my opinion, even people who choose non-traditional publishing benefit from first page critiques. We all want the same thing . . . to write books readers enjoy. So, I'll keep learning what I can about these vexing beginnings. Do they trouble you too? What advice has helped you improve them? I recently tried to explain voice to a non-writer. I mangled the subject badly, prompting this post . . . an attempt to clarify my understanding of the term.

Publishing pros call for books with strong voice, a voice readers can relate to. For me, that voice is the narrator in my head that begins each story (for simplicity, let's assume the main character is always the narrator). The MC whispers a scene. One scene leads to another and as the story develops, so does the character. Their voice grows stronger, more distinct. By the end of the book, I know their history, their quirks, their secret dreams and greatest fears. I know how they talk and move. Most importantly, I know how they view and react to the world. The challenge for writers is to translate the MC's point of view into words. From the opening sentence on the first page, the narrator is on stage. Joan Bauer's Hope Was Here starts: Somehow, I knew my time had come when Bambi Barnes tore her order into little pieces, hurled it in the air like confetti, and got fired from the Rainbow Diner in Pensacola right in the middle of lunchtime rush hour. That sentence defines the narrator as a keen observer and gutsy optimist who's looking for opportunities. I also sense she has a sense of humor from her colorful description of the ticket-shredding incident. Hope's personality, her voice, comes across loud and clear and I know from the opening, I'll love seeing this story through her eyes. Protagonist's voices rise from a writer's experiences and you could say, each are versions of the writer's personality. But in order to fully realize the MC, writer's must be willing to face their own fears, prejudices, and fantasies; to explore unknown territory. The narrator should be free to have habits we dislike and think things we wouldn't. Their voice should speak the story without interference. Writers can't be cowards. Last year, a contemporary book I was working on stalled when I faced scenes I wasn't ready to write. Skimming through them with a watery version of the MC's point of view would have been a waste of time. I've restarted the book and I'm gathering courage. If I can't be true to the voice, I won't have a story worth telling. In children's books, voice must be age appropriate. Many picture book writers capture the youngest readers with lovable characters who do laughable things. Middle grade readers are still dependent on their parents but they expect protagonists who solve their own problems without adult assistance. Middle grade voice is my favorite . . . straddling vulnerabilty, awkwardness, and the edge of maturity. Older teens are strongly influenced by hormones and the need to forge their own path. Most MC's in young adult books deal with love on some level and independence. The young adult voice runs the gamut from sweet to dark and gritty. Unlike those who write for adults, children's writers must tailor their story through a voice authentic to the intended reader. One last thing about voice. Once the book is published, readers bring their voice to the page and how they experience the story is out of your control. At an SCBWI conference, author and creative motivational speaker Lisa McCourt shared her poem about the reader's voice. In it she says : . . . It is your voice saying, for example, the word barn that the writer wrote but the barn you say is the barn you know or knew. |

AuthorI write middle grade and young adult books with a magical twist, and I'm represented by the fabulous Leslie Zampetti at Open Book Literary. Writer Websites

Augusta Scattergood Maggie Stiefvater Rob Sanders Fred Koehler JC Kato Sarah Aronson Kelly Barnhill Linda Urban Kate DiCamillo Jacqueline Woodson Helpful Links SCBWI Agent Query Lorin Oberweger - Freelance Editor Search BlogArchives

May 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed