Yesterday, I finished the fifth revision on my work-in-progress and sent if off to three invaluable readers. While I wait for their feedback, I'm pondering all I've gained from this book. Each novel is a journey. I learned the basics writing my first book. I knew nothing. Not point of view or how to format dialog or why all that lovely description puts young readers to sleep. I was as unpolished and new as new could be. When I started this book, I had a couple conferences behind me. My writing toolbox seemed adequate, my confidence boosted by a contest win and a published story. But I was without a writing group and one-hundred pages in, I sent the manuscript off for professional review. Although the feedback was positive, the suggestions called for a rewrite I couldn't comprehend. My brain twisted into a knot trying to sort it out. In the end, I shelved the project and my creativity spiraled. A year later, I was accepted into a most wonderful critique group. The story, of course hadn't let go of my brain. It had percolated into a nice, bubbly stew, begging to be restarted. So I did, ignoring the old version entirely. What I've written since doesn't even resemble it. And although I couldn't follow the professional's advice because I scrapped what she'd read, I did finally accept her wisdom and I think my work benefitted from it. So the first thing I learned during that painful year was even through the dry spells, there's growth. Just keep writing, keep trying, even if it feels like the worst writing you'll ever do. Even if it ends up in junk files. Write. Another year has passed. I've written and revised the book and added to my toolbox. My critique partners challenge me to craft better sentences and paragraphs, to choose the right words and place them carefully. I listen now to the rhythms in the story, think about syntax and cringe at discords. My previously unstructured chapters now follow arcs, or they try to anyways, and my story strives to hit prescheduled points on a plot map: binding, low and turning. When I think of all I've learned through the writing of this book, I imagine my brain as a house with doors and windows wide open and knowledge sifting through. The greatest things is, the doors and windows didn't close when the book was finished. I'm primed for the next story, ready to learn what it has to teach.

0 Comments

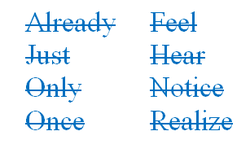

This week, I finished the third draft of my novel, the one I hoped to pass on to readers. But the pile of notes I jotted during that revision demand a fourth attempt. So I've outlined by chapter the additions and changes and next week, I'll attack Draft #4. Writing a book can seem like an endless project. When I've described the process to non-writer friends, they gawk at me and say things like, "Why would anyone go to all that trouble?" Which, believe me, I've asked myself a time or two. Even if your loved ones are supportive, they probably don't understand the passion (some would say madness) that leads us to toil for eons on a story. So, it's best to share writerly moments with people who can relate. The writers in my circle are always willing to lift their heads from their work to encourage and advise. And keep me grounded. Even if I can't see the end of this process, I trust their promise that it does have an end. Books on craft are also a comfort and fuel while I revise. They stimulate the brain and, I hope, affect the revision in a positive way. Recently, I read Donald Maass' The Fire in Fiction. Maass is the president of Donald Maass Literary Agency and the author of Writing the Breakout Novel. In the last chapter of The Fire in Fiction, he addresses what he feels is the lack in most people's writing. Maass writes: Where so many manuscripts go wrong is that, if they do not outright imitate, they at least do not go far enough in mining the author's experience for what is distinctive and personal. That was an eye-opening bit of wisdom. I've joined in discussions about bad writing practices in successful, sometimes award-winning books. We struggle to erase excess adverbs and adjectives, passive voice, telling, etc. from our manuscripts, then pick up the latest publishing darling and gasp at the undisciplined writing. It can be downright discouraging. Some might even see it as an excuse to ignore the experts' list of no-nos. Indeed, after reading truckloads of submissions in his career, Maass suggests the key to a good story is not following all the literary rules, but being as honestly unique as you can. Filter your story through the treasure of memories in your head. Make it a story only you can tell because only you know how you would experience it. I believe that's what agents and editors mean when they say they're looking for fresh voices. And as a reader, I agree with him. If I'm swept up in a story, I don't notice how it's written. I don't think Maass is saying we should stop improving our craft. The creative people I know never tire of learning new ways to improve their work. Writing a novel, for most of us, is a slow process. It requires patience and perseverance, qualities I hope to spend the rest of my life practicing. And next week as I revise, I'm reminded by Maass to leave my individual stamp on the story. Photo credit: David Banghart 2013  Last week, I finished the second full revision of my manuscript. Last weekend, I started word searches for problem words and finished that search around 2:30 this fine Friday afternoon. My eyes are bleary from staring at words like know, hear and feel, pesky filters that slip into our work and dilute the action. Then there are the prepositions, so necessary to sentence construction but oh my how they do pile up on a page: as and when are two of my worst offenders. As I scrolled through the work, I added pet words to my list, like stiff, step, focus and maybe. Reining in the word first, I discovered my character has many first times. Is it possible she's that naïve? Or am I a little too fond of that phrase? And her heart is cited so often, I worried about the health of that organ. At some point I realized (also a filter), I was replacing troublesome words with other troublesome words, as with when, feel with seem . . . you get the picture. So I squared my shoulders, took aim at the culprits and hit the delete key, erasing whole sentences if I must to eradicate the problem. By the time I finished, over a thousand words had been erased. I sat back, shell-shocked from a week of word war. I hope next week when I sit down in this chair to begin the third revision, I won't see a hole-riddled manuscript with passages that don't make sense. But seriously, I think this was a valuable exercise and worth every writer doing at least once. You'll come away knowing what words and phrases you overuse. It challenges you to not lean on familiar crutches, to find new ways of expressing the thoughts in your head. The bolded words in this post are all on my list. What repetitive words are on yours?  What is your writing process? I mean the physical process of turning your story into a document. Four and a half years ago, I sat down with a spiral-bound notebook and began writing a story. I filled that notebook and another and another with my first book. Then I joined a critique group which required legible copies of my chapters. Thus began my love/hate relationship with the computer. The critiqued chapters stacked up. I noted the suggestions in a revision notebook. Then I sat down with a printed copy of the manuscript, the revision notebook and a pen. I scribbled changes in the white space, slogged back to the computer and pecked at the keyboard. That first book was rewritten a few times and I considered it a learning experience. As my writing grew, my process changed. I kept a notebook for each book, others for short stories and queries but each week I entered the new material into the computer. I gradually abandoned the notebooks and for the last couple years, most of my work is typed on the keyboard. I still use the notebooks to jot story ideas and sometimes story beginnings but after a page or two, I'm cozied up to Microsoft. I feel like a sell-out, somehow. I'm a hands-on, creative type. I enjoy art touched by fingers and homemade crafts. I admire writers who wrote books by hand and poked at clackety typewriters. Several months back, I hit a wall in my writing and nothing I tried knocked it down, not plotting or character studies, not switching stories or genres, not even taking a break. Then I thought, why not go back to your beginning, dust off the notebooks, step away from the computer. It wasn't an instant fix but that notebook felt like an old friend and I did write in it. Now, I'm trying to stay conscious of my nature, take mini-vacations from technology and reconnect with pen and paper. I'm blessed to have a husband who loves story as much as I do. He grew up in a reading household and he keeps a book within reach at all times. He also has a flexible mind. Which is a huge asset when I need to plot story.

I like to brainstorm away from the distractions of home. We walk a couple miles every morning and story often accompanies us. It usually starts with a plot point; a snag or stall. This morning, I had reenvisioned the beginning of a YA book. I shared it with my husband and we began to fill in the empty spaces. Birds trilled, frogs croaked, and peafowl honked. We automatically waved at passersby leaving for work. Our feet carried us down the path, while our minds plotted story. We stopped briefly to check out the creek, flowing after recent rains, and again the marshy field where last week we spotted a mallard and her seven ducklings. Then our chat continued to the rhythm of our steps. The subject was apocalyptic. When I finally looked up several houses from our home, I laughed at us, the frumpy, middle-aged couple plotting the worlds' destruction on our bucolic walk. Sometimes, we brainstorm story in the car, losing track of our destination until one of us blinks at the road and announces, "We missed the turn!" At the cafe where we like to eat breakfast, I force myself to focus on the waitress until our order is served. Then story is tossed across the table, seasoning our food with plot. It's no wonder so many authors acknowlwdge their spouses and children on the inside covers of books. Family--good listeners and eager plotters--deserve credit for their part in the story. In April I attended a workshop led by author and writing coach extraordinaire, Joyce Sweeney. The workshop focused on character but Joyce also critiqued first pages. Since many attend summer conferences where first pages are often reviewed, I thought I'd share what I learned from Joyce about that all-important start to a book.

This is my fifth year dedicated to learning to write and beginnings still feel like my nemesis. I revisit them repeatedly, experience "aha" moments when I think I've found the perfect opening only to see it dashed in critique. How do you accomplish all that's required in two-hundred and fifty words? Readers need to meet the protaganist and it isn't a casual introduction. They want to know their personality, age, their goal and conflict, where they live and when. They might also meet secondary characters. They'll need to know their relationship to the main character and what distinquishes them. For that reason, I try to keep the characters on the first page to a minimum. You don't want readers scratching their heads over who's who. On top of all that, the opening reveals the event that changes everything for the MC, the moment that sets the story in motion. That moment might be your HOOK! (yes, it is spoken in capitals. With an exclamation mark). Writers learn early about the need to snatch readers and reel them in. Huge units of brain power are burned trying to create irresistible openings. You have one, maybe two paragraphs to convince readers to buy your book. So, you promise thrills or chills or mind-shifting worlds. Which brings me to the first new tidbit I gleamed from Joyce's feedback: Genre should be evident from the start. If you're writing a ghost story, introduce spooky; if it's dystopia, show us the altered world; if contemporary, place us in the now. This is something I've ignored. I focused on character, conflict and setting, expecting readers to discover genre on the next pages. It's seems obvious now . . . if I'm expecting sci-fi and I find none on the first page, why would I read the book? The second discovery I made at the workshop was about character introduction. Readers need to relate to the main character, even want to be the character. So Joyce advised against showing their big flaw on the first page. The example she read opened with a protagonist who vomited when she was nervous . . . and she did it on the first page. It was a well-written scene but would you turn that page? You want the reader to like/admire/feel-compelled-to-follow the character before you introduce flaws that make them gag on the chocolate they're munching. First page reviews at conferences and workshops offer authors professional feedback. Eventually, your book will be submitted to agents and publishers and the industry is too overworked to read past a manuscript's unimpressive start. In my opinion, even people who choose non-traditional publishing benefit from first page critiques. We all want the same thing . . . to write books readers enjoy. So, I'll keep learning what I can about these vexing beginnings. Do they trouble you too? What advice has helped you improve them?  Look at that . . . there's blue sky and trees out there! I've been huddled over the computer for fourteen straight days, finishing ninety pages and a synopsis to send to my mentor, Caroline Leavitt. Today, I printed them and tomorrow I'll mail the package. It was so cool to see that stack of printed paper, the beginnings of a real book. It feels like an accomplishment. It's hard to get that sense from a computer file. Two weeks ago, Caroline said to send the messy draft but I couldn't do it. The story had changed too much since I started. Plot lines had veered and I worried it wouldn't make sense. I thought, I'll just zip in there and tidy things up, a week, ten days tops, I'll be done. Uh-huh. Once I opened that door, the story took over. It whispered new thoughts, enlightened me about characters' motivations, tweaked scenes. I carried a notebook around, scribbling through the day and night. I'd edit ten pages; then each morning, I'd pull out my notes and revisit scenes. Finally, I stomped my foot, faced the story and hollered, "This isn't supposed to be a real revision!" And so it allowed me to finish what I started but only if I promised to keep taking notes for the REAL REVISION. Day before yesterday, I faced the synopsis with headache-inducing dread. I started this book without an outline and so far the story's unfolded chapter by chapter. I have a clear image of the ending but the unwritten chapters in between are up in the air. After one-hundred pages, I feel I'm just getting to know my characters. The story arc isn't complete and it's unclear how conflicts will be resolved. I wasn't sure how to approach the synopsis and I can only hope what I wrote makes sense. As uncomfortable as the experience was, I'm glad to have attempted it at this stage. I think it will help when it's time to write one for queries. This afternoon, I'm taking a break to catch up on friends' blogs and write this post. Tomorrow, I owe everyone and their brother an email. Friday, I pick up where I left off . . . Page 91. |

AuthorI write middle grade and young adult books with a magical twist, and I'm represented by the fabulous Leslie Zampetti at Open Book Literary. Writer Websites

Augusta Scattergood Maggie Stiefvater Rob Sanders Fred Koehler JC Kato Sarah Aronson Kelly Barnhill Linda Urban Kate DiCamillo Jacqueline Woodson Helpful Links SCBWI Agent Query Lorin Oberweger - Freelance Editor Search BlogArchives

May 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed